Adenomatous Colon Polyps

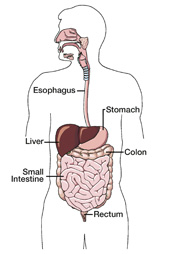

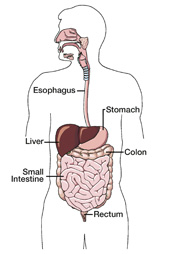

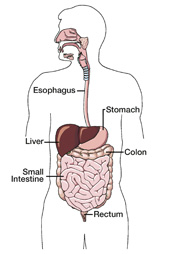

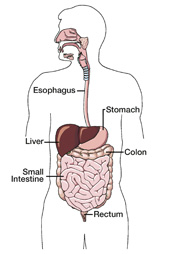

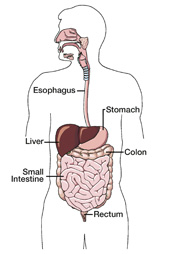

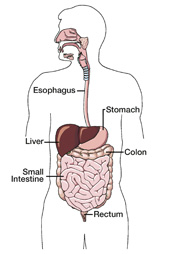

| The colon, or large intestine, is a tube lined with muscles that extracts moisture and nutrients from food, storing the waste matter until it is expelled from the body. It is typically 5 to 6 feet long in adults. The last segment of the colon is called the rectum. Polyps are small clusters of extra tissue that form on the lining of the colon. These growths often resemble the cap of a mushroom and project outward from the wall of the intestine. Anyone can develop colon polyps, and about 20% of adults who are middle-aged and older have one or more polyps. Risk factors include:

Nearly 90% of all colon polyps are hyperplastic polyps, which People with adenomatous colon polyps often have no symptoms of their condition, although some may experience rectal bleeding, ongoing changes in bowel habits or abdominal pain. |

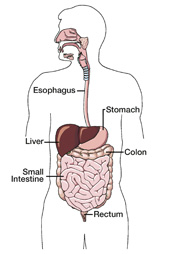

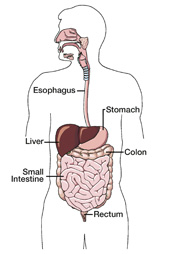

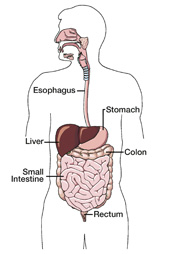

Atrophic Gastritis

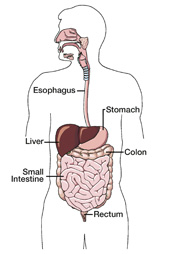

| The stomach is a hollow, muscular pouch in the upper-left region of the abdomen, typically Atrophic gastritis usually occurs as the result of chronic gastritis, a condition most often caused by H. pylori infection that weakens the protective mucous layer of the stomach and allows gastric acid to reach and damage the stomach lining. Because atrophic gastritis develops over a long period of time, People with atrophic gastritis usually have no symptoms, Moreover, people with atrophic gastritis have an increased risk |

The typical treatment plan for atrophic gastritis seeks to reverse the condition by getting

rid of the underlying H. pylori infection, thus decreasing the risk of ulcers and stomach cancer. Often more than one treatment is used at the same time. The following treatment possibilities

are available:

Proton Pump Inhibitors – Medications called proton pump inhibitors seem to hinder the activity of H. pylori bacteria. They are also often used to suppress the production of gastric acid.

Coating Agents – A different type of medication helps protect the tissues that line the stomach

and small intestine. These stomach coating drugs are available by prescription and over the counter (OTC). One such OTC medication is bismuth subsalicylate, which also appears to inhibit

H. pylori activity.

Antibiotics – Antibiotic drugs are used to eliminate the H. pylori infection. Sometimes two different antibiotics are prescribed along with a proton pump inhibitor, called triple therapy, which is a very effective method that kills the bacteria nearly 90% of the time. Patients are often tested after their antibiotic treatment ends to determine if the infection is completely gone.

Vitamin B-12 Injections – A few patients with atrophic gastritis may need to have ongoing injections of vitamin B-12 to prevent or reverse the development of pernicious anemia.

To reduce the symptoms of atrophic gastritis and prevent other digestive problems, you should avoid potential stomach irritants such as smoking, caffeine, alcohol and highly seasoned foods.

You can eat smaller, more frequent meals to buffer stomach acid secretion. Be sure to wash your hands thoroughly too, especially at mealtimes and after using the bathroom, since H. pylori bacteria are contagious.

In addition, pain relievers containing acetaminophen are generally recommended to use instead of aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and naproxen. Talk with your doctor about what prescription and OTC medications are best for your individual situation. Also be sure to tell your doctor if your symptoms get worse or linger.

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 800.891.5389, www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc

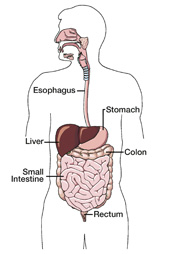

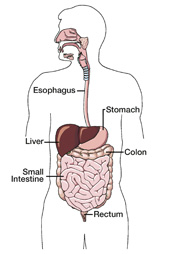

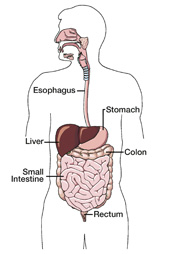

Barrett's Esophagus – High Grade

| After completing a thorough lab analysis of your recent esophageal biopsy, a specialized doctor called a pathologist reported a diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus–with high grade dysplasia, a pre-cancerous condition of the esophagus. Barrett’s esophagus is relatively uncommon, affecting about 700,000 adults in the U.S. with an average age of diagnosis of 60. It occurs about twice as often in men than women, and most frequently in Caucasians.

Barrett's esophagus occurs when the cells lining the lower The condition most often arises from ongoing gastroesophageal Heartburn is the most notable symptom of acid reflux and GERD. Almost everyone has experienced the burning pain of heartburn at some point, but people with GERD endure it on a continuing basis because of a weakened lower esophageal sphincter. In contrast, Barrett’s esophagus patients seldom have symptoms, although a few experience trouble swallowing, bloody vomit or stools, or weight loss. Frequently, people with Barrett’s esophagus recall having episodes of heartburn in the past, but not in recent years |

The treatment plan for Barrett’s esophagus generally depends on whether or not dysplasia is present, and the grade of the dysplasia if present. Because low-grade dysplasia does not develop into esophageal cancer without first progressing to the high-grade stage, patients with high-grade Barrett’s esophagus require more aggressive therapy.

The following treatment possibilities are available:

Everyday Changes – People with Barrett’s esophagus can diminish symptoms by making specific lifestyle changes that help lessen stomach acid reflux. This may include losing weight, taking part in some form of exercise, avoiding certain foods and elevating the head of the bed.

Medication – Drug therapy for Barrett’s esophagus helps prevent acid reflux and relieve irritated tissues, but does not appear to decrease the risk of esophageal cancer. Medications used include acid blockers and proton pump inhibitors. Acid blocking drugs — often referred to as histamine or H2 blockers — work by decreasing the amount of acid the stomach produces. Proton pump inhibitors are even more powerful at suppressing gastric acid and work by stopping the action of acid “pumps” within specific stomach cells.

Surgery – Operations to treat Barrett’s esophagus are sometimes performed. Anti-reflux surgery eliminates the symptoms of reflux by wrapping part of the stomach around the bottom of the esophagus to tighten the lower sphincter. Esophagectomy, the removal of the entire esophagus and repositioning of the stomach into the chest, is occasionally done in patients with high-grade Barrett’s esophagus who have an elevated risk of developing cancer.

Ablation Procedures – The removal, or ablation, of diseased esophageal tissue is another form

of treatment for Barrett’s esophagus. Ablation procedures include photodynamic therapy, electrocautery and argon plasma coagulation. In photodynamic therapy, abnormal cells are burned off by a laser light after being illuminated by a photosensitizing drug. In electrocautery, diseased cells are destroyed using an electric wire. A jet of argon gas and electric current are used in argon plasma coagulation to burn away esophageal dysplasia. The long-term effectiveness of ablation procedures is currently being studied.

To reduce the symptoms of reflux and prevent other digestive problems, you should avoid potential stomach irritants such as smoking, alcohol, coffee, chocolate and fatty or highly seasoned foods. You should eat smaller, more frequent meals that are high in fruits and vegetables. You can also use over-the-counter antacids to neutralize stomach acid.

In addition, pain relievers containing acetaminophen are generally recommended to use instead of aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and naproxen. Talk with your doctor about what prescription and over-the-counter medications are best for your individual situation. Your doctor will likely schedule periodic exams and biopsies to monitor for the early warning signs of esophageal cancer, as well

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

Cancer Consultants Oncology Resource Center, http://cancerconsultants.com

Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 800.891.5389, www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc.

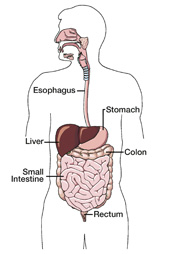

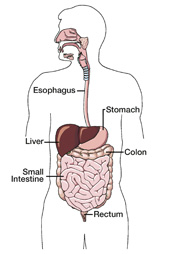

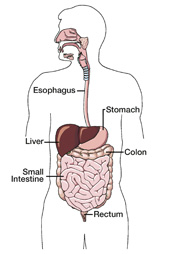

Barrett's Esophagus – Low Grade

| After completing a thorough lab analysis of your recent esophageal biopsy, a specialized doctor called a pathologist reported a diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus with low grade dysplasia , an early stage

Barrett's esophagus occurs when the cells lining the lower The condition most often arises from ongoing gastroesophageal Heartburn is the most notable symptom of acid reflux and GERD. Almost everyone has experienced the burning pain of heartburn at some point, but people with GERD endure it on a continuing basis because of a weakened lower esophageal sphincter. In contrast, Barrett’s esophagus patients seldom have symptoms, although a few experience trouble swallowing, bloody vomit or stools, or weight loss. Frequently, people with Barrett’s esophagus recall having episodes of heartburn in the past, but not in recent years. |

The treatment plan for Barrett’s esophagus generally depends on whether or not dysplasia is present, and the grade of the dysplasia if presentits grade. Because low-grade dysplasia does not develop into esophageal cancer without first progressing to the high-grade stage, patients with high-grade Barrett’s esophagus require more aggressive therapy.

The following treatment possibilities are available:

Everyday Changes – People with Barrett’s esophagus can diminish symptoms by making specific lifestyle changes that help lessen stomach acid reflux. This may include losing weight, taking part in some form of exercise, avoiding certain foods and elevating the head of the bed.

Medication – Drug therapy for Barrett’s esophagus helps prevent acid reflux and relieve irritated tissues, but does not appear to decrease the risk of esophageal cancer. Medications used include acid blockers and proton pump inhibitors. Acid blocking drugs — often referred to as histamine or H2 blockers — work by decreasing the amount of acid the stomach produces. Proton pump inhibitors are even more powerful at suppressing gastric acid and work by stopping the action of acid “pumps” within specific stomach cells.

Surgery – Operations to treat Barrett’s esophagus are sometimes performed. Anti-reflux surgery eliminates the symptoms of reflux by wrapping part of the stomach around the bottom of the esophagus to tighten the lower sphincter. Esophagectomy, the removal of the entire esophagus and repositioning of the stomach into the chest, is occasionally done in patients with high-grade Barrett’s esophagus who have an elevated risk of developing cancer.

Ablation Procedures – The removal, or ablation, of diseased esophageal tissue is another form

of treatment for Barrett’s esophagus. Ablation procedures include photodynamic therapy, electrocautery and argon plasma coagulation. In photodynamic therapy, abnormal cells are burned off by a laser light after being illuminated by a photosensitizing drug. In electrocautery, diseased cells are destroyed using an electric wire. A jet of argon gas and electric current are used in argon plasma coagulation to burn away esophageal dysplasia. The long-term effectiveness of ablation procedures is currently being studied

To reduce the symptoms of reflux and prevent other digestive problems, you should avoid potential stomach irritants such as smoking, alcohol, coffee, chocolate and fatty or highly seasoned foods. You should eat smaller, more frequent meals that are high in fruits and vegetables. You can also use over-the-counter antacids to neutralize stomach acid.

In addition, pain relievers containing acetaminophen are generally recommended to use instead of aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and naproxen. Talk with your doctor about what prescription and over-the-counter medications are best for your individual situation. Your doctor will likely schedule periodic exams and biopsies to monitor for the early warning signs of esophageal cancer, as well

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

Cancer Consultants Oncology Resource Center, http://cancerconsultants.com

Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 800.891.5389, www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc.

Collagenous Colitis

| After completing a thorough lab analysis of your recent colon biopsy, a specialized doctor called a Pathologist reported a diagnosis of collagenous colitis, an ongoing (chronic) inflammation of the colon. Collagenous colitis does not increase the risk of developing colon cancer, and it is Collagenous colitis is a rare condition that falls under the broad category of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It most often affects people between the ages of 50 and 70, and occurs about

Collagenous colitis occurs when a thicker than normal band of The inflammation of collagenous colitis is not visible when No one knows exactly what causes collagenous colitis, but the Many patients with collagenous colitis have other autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, thyroid disease, pernicious anemia (the inability to absorb vitamin B-12 from the gastrointestinal tract), or celiac disease, a digestive condition caused by intolerance to gluten, a protein found in foods including wheat and rye. Collagenous colitis is not life-threatening; however, heavy diarrhea caused by the condition can sometimes lead to severe dehydration, malnutrition and weight loss |

The treatment plan for collagenous colitis often depends on the severity of the condition. The following treatment possibilities are available:

Everyday Changes – Although food is not a direct cause of collagenous colitis, people with the condition can diminish symptoms by eating a low-fat diet that is high in fruits, vegetables and fiber and avoiding caffeine and dairy products. It is also helpful to avoid the use of NSAIDs.

Medication – A variety of medications can be used to treat collagenous colitis. They include drugs to control diarrhea, anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics and corticosteroids, which are primarily prescribed to patients who do not respond well to other medications.

Surgery – In very rare and severe cases of collagenous colitis, a colon resection to remove part of the large intestine, or a colectomy to remove it entirely, may be performed.

You can choose to take an active role in your health and well-being. Learn as much as you can about your condition and have a list of questions ready each time you meet with your doctor. Join a support group for IBD, and talk with your family, friends or counselor as you feel comfortable.

Other steps you can take to maximize your health include:

- Burning up all of the calories you take in each day through healthy eating and regular exercise

- Minimizing stress by getting enough sleep every night and using relaxation techniques

- Cutting out the use of tobacco and limiting your alcohol consumption

- Visiting your doctor regularly and promptly reporting any new symptoms that develope

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America, 800.932.2423, www.ccfa.org

Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 800.891.5389, www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc

Colorectal Cancer

| After completing a thorough lab analysis of your recent biopsy, a specialized doctor called a pathologist reported a diagnosis of colorectal cancer, or cancer that begins in the colon or the rectum. Colorectal cancer is the third most common form of cancer in the western world. It occurs equally in men and women, and most frequently in African-Americans. The risk of developing the condition increases greatly after age 50, and the average age of diagnosis is 66.

The colon, or large intestine, is a tube lined with muscles that extracts moisture and nutrients from food, storing the waste matter until it is expelled from the body. It is typically 5 to 6 feet long in adults. The last segment of the colon is called the rectum.

Cancer occurs when cells in the lining of the colon or rectum do not develop and die in their normal manner. The extra cells that result form a growth, or tumor, which can be benign or malignant. Benign tumors are not cancer and do not spread throughout the body. Malignant tumors are cancer. Their cells may invade and damage surrounding areas or spread to other locations in the body (metastasize). About 95% of colorectal tumors begin as a type of polyp called an adenoma, a pre- cancerous growth that projects outward from the intestinal wall.

Colorectal cancer usually grows at a slow pace, but at times it can develop and metastasize quickly. Your doctor may want to perform one or more tests to help determine if the cancer has spread, which could include the following:

Cancer that is confined within the intestinal wall is the most manageable and curable. If malignant cells extend through the intestine into surrounding tissues, lymph nodes or other areas of the body the treatment plan will be more complex and the cancer may not be curable. Many treatment options are available for patients with incurable colorectal cancer to help minimize pain and improve quality of life. Talk with your doctor about your specific stage of cancer. |

Deciding on a treatment plan for your colorectal cancer can be complex and depend upon a variety of factors, such as your age, general health condition, stage of cancer and personal preferences. Sometimes more than one type of therapy may be used.

The following treatment possibilities are available:

Surgery – The main form of treatment for colorectal cancer is surgery. When cancer is confined to a polyp, patients undergo a polypectomy or a local excision, which also removes a small amount of adjacent tissue. When cancer has spread into the intestinal wall or surrounding tissues, a partial resection is done to remove the tumor, part of the intestine and nearby lymph nodes. The intestine is then reconnected. When that is not possible, a colostomy is created to allow waste to leave the body through the abdominal wall to be collected in a bag. Sometimes a temporary colostomy is done to give the intestine time to heal before being reconnected.

Radiation Therapy – Another common treatment method is radiation therapy, which can be delivered externally or internally. In external beam radiation — most often used to treat colorectal cancer — a high energy X-ray machine is used to direct radiation at the tumor. Internal radiation therapy destroys cancer cells with small implants that are placed directly into the tumor.

Chemotherapy – The use of anti-cancer drugs, or chemotherapy, provides a way to slow tumor growth and reduce pain for patients whose cancer has spread outside of the large intestine. It also can help prevent the recurrence of surgically removed tumors. One particular method of chemotherapy called downstaging is sometimes used to shrink a tumor to make it surgically removable or to eliminate the need for a post-operative colostomy.

Biologic Therapy – Newer therapy methods that employ man-made biologics are being used to treat colorectal cancer. These biologics, or synthetic proteins, are called monoclonal antibodies. They work by targeting specific proteins found on tumor cells.

You may also consider participating in clinical trials. These investigative studies help doctors learn about new treatments and better ways to use established treatments. Talk with your doctor about the possibility of taking part in a clinical trial in your area

You can choose to take an active role in your health and well-being. Learn as much as you can about your condition and have a list of questions ready each time you meet with your doctor.

Join a cancer support group, and talk with your family, friends, clergyperson or counselor as you

feel comfortable. Also, be sure to get enough sleep every night.

Other steps you can take to maximize your health include eating a low-fat diet high in fruits and vegetables, avoiding the use of tobacco, limiting consumption of alcohol and red meat, taking part in some form of exercise and maintaining a healthy body weight

American Cancer Society, 800.227.2345, www.cancer.org

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

National Cancer Institute, 800.422.6237, www.cancer.gov

Oncology Channel, www.oncologychannel.com

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc.

Esophageal Cancer

| After completing a thorough lab analysis of your recent biopsy, a specialized doctor called a pathologist reported a diagnosis of esophageal cancer, or cancer that begins in the esophagus. Esophageal cancer affects men 3 to 4 times more often than women, and occurs most frequently in African-Americans.

The esophagus is a tube lined with muscles that contracts to transport food and liquids from the mouth to the stomach. The upper and lower ends of the esophagus are clamped together by specialized muscles, called sphincters. Normally the lower sphincter opens automatically to let food pass into the stomach and closes quickly to prevent stomach contents and acid from leaking back into the esophagus, or refluxing.

Cancer occurs when cells in the lining of the esophagus do not develop and die in their normal manner. Contributing factors may include excessive use of tobacco or alcohol and ongoing acid reflux conditions such as Barrett’s esophagus. The extra cells that result form a growth, or tumor, which can be benign or malignant. Benign tumors are not cancer and do not spread throughout the body. Malignant tumors are cancer. Their cells may invade and damage surrounding areas or spread to other locations in the body (metastasize).

Adenocarcinoma, the most common form of esophageal cancer, affects the lower esophagus, while squamous cell carcinoma involves the middle and upper sections. Because the condition is often diagnosed at a later stage, your doctor may want to perform one or more tests to help determine if the cancer has spread, which could include the following:

Cancer that is confined within the esophageal wall is the most manageable and curable. If malignant cells extend through the esophagus into surrounding tissues, lymph nodes or other areas of the body, the treatment plan will be more complex and the cancer may not be curable. Many treatment options are available for patients with incurable esophageal cancer to help minimize pain and improve quality of life |

Deciding on a treatment plan for your esophageal cancer can be complex and depend upon a variety of factors, such as your age, general health condition, stage of cancer and personal preferences. Sometimes more than one type of therapy may be used.

The following treatment possibilities are available:

Surgery – The main form of treatment for esophageal cancer is surgery. Typically the tumor and part of the esophagus are removed along with surrounding tissues and nearby lymph nodes. Occasionally an esophagectomy is necessary, which involves removal of the entire esophagus and repositioning of the stomach into the chest.

Radiation Therapy – Another treatment method for esophageal cancer is radiation therapy, which can be delivered externally or internally. In external beam radiation, a high energy X-ray machine is used to direct radiation at the tumor. Internal radiation therapy destroys cancer cells with small implants that are placed directly into or near the tumor.

Chemotherapy – The use of anti-cancer drugs, or chemotherapy, provides a way to slow tumor growth and reduce pain for patients whose cancer has spread outside of the esophagus.

Laser and Photodynamic Therapy – Sometimes laser therapy or photodynamic therapy is used to treat esophageal cancer. Laser therapy uses high-intensity light to destroy malignant cells. In photodynamic therapy, abnormal cells are burned off by a specific type of laser after being illuminated by a photosensitizing drug. Both therapies can help relieve difficulty in swallowing.

You may also consider participating in clinical trials. These investigative studies help doctors learn about new treatments and better ways to use established treatments. Talk with your doctor about the possibility of taking part in a clinical trial in your area

You can choose to take an active role in your health and well-being. Learn as much as you can about your condition and have a list of questions ready each time you meet with your doctor.

Join a cancer support group, and talk with your family, friends, clergyperson or counselor as you

feel comfortable. Other steps you can take to maximize your health include:

- Having smaller and more frequent meals throughout the day

- Eating soft, bland and pureed foods if you have trouble swallowing

- Taking part in some form of exercise on a regular basis

- Minimizing stress by getting enough sleep every night and using relaxation techniques

- Visiting your doctor regularly and promptly reporting any new symptoms that develop

Additional Resources

American Cancer Society, 800.227.2345, www.cancer.org

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

National Cancer Institute, 800.422.6237, www.cancer.gov

Oncology Channel, www.oncologychannel.com

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc.

Gastritis

| Your doctor has determined that you have gastritis, an inflammation of the stomach lining.

Gastritis occurs when the protective mucous layer is weakened, allowing gastric acid to reach the stomach lining. Numerous behaviors and underlying conditions can trigger gastritis. One of the most common is the prolonged use of aspirin or non-steroidal Occasionally gastritis develops after a traumatic injury or major Gastritis can be acute, coming on suddenly, or chronic, It is estimated that more than 65% of people in the world are infected with H. pylori, although most of them never suffer any symptoms. In addition to gastritis, H. pylori infection causes ulcers in the stomach and intestinal lining, and increases the risk of developing stomach cancer |

The treatment plan for gastritis generally depends on the cause of the condition. Some treatment choices target the source of gastritis directly while others reduce symptoms, such as excess acid secretion, giving time for the stomach to heal. Often, more than one treatment is used at the

same time.

The following treatment possibilities are available:

Antacids – Patients with mild gastritis can frequently achieve quick pain relief by using over-the-counter (OTC) antacids, which neutralize acid in the stomach.

Acid Blockers – If antacids do not eliminate symptoms, acid-blocking drugs may be recommended. These medications — often referred to as histamine or H2 blockers — work by decreasing the amount of acid the stomach produces. Some are available over the counter; others require

a prescription.

Proton Pump Inhibitors – A more powerful way to suppress gastric acid is to block the stomach’s ability to secrete it with drugs that stop the action of acid “pumps” within specific stomach cells. These proton pump inhibitors also seem to hinder the activity of H. pylori bacteria.

Coating Agents – A different type of medication helps protect the tissues that line the stomach and small intestine. These coating agents are often recommended for patients who take NSAIDs regularly. Stomach coating drugs are available by prescription and over the counter. One such OTC medication is bismuth subsalicylate, which also appears to inhibit H. pylori activity.

Antibiotics – Gastritis that is caused by H. pylori infection is treated with antibiotics. Sometimes two different antibiotics are prescribed along with a proton pump inhibitor, called triple therapy, which is a very effective method that kills the bacteria nearly 90% of the time. Patients whose gastritis is caused by H. pylori are often tested, after their antibiotic treatment ends, to determine if the infection is completely eliminated

To reduce the symptoms of gastritis and prevent other digestive problems, you should avoid potential stomach irritants such as smoking, caffeine, alcohol and highly seasoned foods. You can eat smaller, more frequent meals to buffer stomach acid secretion. Be sure to wash your hands thoroughly too, especially at mealtimes and after using the bathroom, since H. pylori bacteria

are contagious.

In addition, pain relievers containing acetaminophen are generally recommended to use instead of aspirin and NSAIDs. Talk with your doctor about what prescription and OTC medications are best for your individual situation. Also be sure to tell your doctor if your symptoms get worse or linger.

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 800.891.5389, www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc

Gastroesophageal Refiux Disease

| Your doctor has determined that you have gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD, a condition marked by ongoing stomach acid reflux and inflammation of the lower esophagus. GERD is a very common disorder that affects more than 60 million American adults. It can also occur in infants and children.

GERD occurs when acid reflux is frequent or constant and inflames the lower esophagus. The most common symptom is heartburn, a burning pain in the chest that may spread to the neck. Almost everyone has experienced heartburn at some point, but most GERD patients endure it on a continuing basis because of a weakened lower esophageal sphincter. Other symptoms of the condition may include a dry cough, Contributing factors to GERD include: Lifestyle – such as being overweight, eating large meals, lying Medications – including some blood pressure drugs, Other Medical Conditions – such as pregnancy, diabetes and If GERD is left untreated, it can lead to other conditions. About 10% of people who suffer from severe GERD over a period of years develop Barrett’s esophagus. This pre-cancerous condition results from damage to the cells lining the esophagus, but only rarely progresses into GERD can also sometimes cause esophageal ulcers, or open sores, which may bleed and be painful. In addition, GERD can lead to narrowed areas, or strictures, in the esophagus, which are formed by scar tissue and can interfere with swallowing |

The typical treatment plan for GERD seeks to reverse the condition by stopping the acid reflux. The following treatment possibilities are available:

Everyday Changes – Patients can diminish symptoms by making specific lifestyle changes that help lessen stomach acid reflux. This may include losing weight, taking part in some form of exercise, avoiding certain foods and elevating the head of the bed.

Medication – A variety of medications can be used to treat GERD, including antacids, acid blockers and proton pump inhibitors. Some patients can achieve quick pain relief by using over-the-counter (OTC) antacids, which neutralize acid in the stomach. Acid blocking drugs — often referred to as histamine or H2 blockers — work by decreasing the amount of acid the stomach produces. Proton pump inhibitors are even more powerful at suppressing gastric acid and work by stopping the action of acid “pumps” within specific stomach cells.

Surgery – In rare cases when symptoms do not respond to drug therapy, anti-reflux surgery may be performed to treat GERD. The operation eliminates acid reflux by wrapping part of the stomach around the bottom of the esophagus to tighten the lower sphincter. This procedure is sometimes performed using a few small abdominal incisions to provide access for a camera, or laparoscope, and surgical instruments.

To reduce the symptoms of reflux and prevent other digestive problems, you should avoid potential stomach irritants such as smoking, alcohol, caffeine, chocolate, peppermint and fatty or highly seasoned foods. You should also eat smaller, more frequent meals that are high in fruits and vegetables, with the exception of citrus and tomato products.

Other steps you can take to maximize your health and minimize symptoms include:

- Waiting at least 3 hours after you eat before lying down

- Maintaining a healthy body weight

- Drinking plenty of liquid when taking medications

- Wearing loose fitting clothing without belts

- Visiting your doctor regularly and promptly reporting any new symptoms that develop

In addition, pain relievers containing acetaminophen are generally recommended to use instead of aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and naproxen. Talk with your doctor about what prescription and OTC medications are best for your individual situation

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 800.891.5389, www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc

H. Pylori Infection

| Your doctor has determined that you are infected with Helicobacter pylori bacteria, which is a relatively common condition. In the U.S., some 20% of people under the age of 40 and half of

H. pylori are spiral-shaped bacteria that are found in the stomachs of infected persons and can be transmitted between people. These bacteria are the cause of most cases of chronic stomach inflammation (gastritis) as well as ulcers, or sores, in the lining of the stomach and the duodenum, which is the top part of the small intestine. In addition, H. pylori infection increases the risk of stomach cancer if left untreated. Although common in the U.S., H. pylori infection occurs more

H. pylori infection causes ulcers to form when the bacteria Although the majority of ulcers are caused by H. pylori infection, they can also be caused by the use of aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and naproxen |

The typical treatment plan for H. pylori infection uses medication to eliminate the bacteria causing the infection and includes one or more other drugs to protect the stomach lining and reduce symptoms such as excess acid secretion.

The following treatment possibilities are available:

Antibiotics – Antibiotics are commonly used to kill the bacteria causing H. pylori infection. In most cases, two different antibiotics are prescribed along with a proton pump inhibitor, called triple therapy, which is a very effective method that kills the bacteria nearly 90% of the time.

Acid Blockers – Acid-blocking medications — often referred to as histamine or H2 blockers — work by decreasing the amount of acid the stomach produces. Some are available over the counter (OTC); others require a prescription.

Proton Pump Inhibitors – A more powerful way to suppress gastric acid is to block the stomach’s ability to secrete it with drugs that stop the action of acid “pumps” within specific stomach cells. These proton pump inhibitors also seem to hinder the activity of H. pylori bacteria.

Coating Agents – A different type of medication helps protect the tissues that line the stomach

and small intestine. These coating agents are often recommended for patients who take NSAIDs regularly. Stomach coating drugs are available by prescription and over the counter. One such OTC medication is bismuth subsalicylate, which also appears to inhibit H. pylori activity.

Once the H. pylori bacteria are eliminated after treatment, the chance of recurrence is very low. Additionally, researchers are working to develop a vaccine to prevent H. pylori infection

To reduce any symptoms of H. pylori infection that you may have and prevent other digestive problems, you should avoid potential stomach irritants such as smoking, caffeine and alcohol. You can also eat smaller, more frequent meals to buffer stomach acid secretion. Be sure to wash your hands thoroughly too, especially at mealtimes and after using the bathroom, since H. pylori bacteria are contagious.

In addition, pain relievers containing acetaminophen are generally recommended to use instead of aspirin and NSAIDs. Talk with your doctor about what prescription and OTC medications are best for your individual situation. Also be sure to tell your doctor if your symptoms get worse or linger

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 800.891.5389, www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2006 CBLPath, Inc

Hepatitis C

| Your doctor has determined that you have hepatitis C, a liver disease caused by infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). In the U.S., hepatitis C is the most common chronic blood-transmitted disease, with some 4 million people infected with HCV and more than 25,000 new cases

Hepatitis C occurs when the liver becomes inflamed due to infection with HCV. Most people who contract hepatitis C do not have any initial symptoms. Sometimes they may experience mild fatigue, fever, headache, nausea or abdominal pain. The hepatitis C virus is usually transmitted through direct Sometimes hepatitis C is spread through unprotected sexual In addition, people who received long-term kidney dialysis, Occasionally people with HCV spontaneously clear the infection in its early stages; however, up to 85% of patients have a chronic, or life-long, infection. The disease usually progresses slowly, and can cause permanent liver damage over a period of 20 to 30 years. About 1 out of 5 hepatitis C patients develop cirrhosis, or scarring, of the liver. Liver failure and liver cancer are end-stage complications of hepatitis C that can arise, most often in patients with cirrhosis. Nearly half of all liver transplants in the U.S. are performed on patients with end-stage hepatitis C. |

Antiviral medications are often used to treat hepatitis C, but they are not suitable for all patients. Your doctor will monitor your condition and determine what is most appropriate for your specific case. You may need a liver biopsy to check the extent of damage to your liver.

Two main drugs are used to treat hepatitis C — pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Sometimes interferon is used alone, but most often it is prescribed together with ribavirin. This combination therapy is generally considered the treatment of choice for hepatitis C.

To establish the best individual treatment plan before starting drug therapy, it is important to determine which hepatitis C genetic category, or genotype, a patient carries. There are 6 distinct HCV genotypes, with genotype 1 being the most common in the U.S. It is possible for a person to be infected with more than one genotype at the same time

You can choose to take an active role in your health and well-being. Learn as much as you can about your condition and see your doctor on a regular basis. You may also want to join a support group for people with hepatitis C. Other steps you can take to maximize your health include:

- Eating a healthy diet and avoiding alcohol, which can speed up liver damage

- Having smaller and more frequent meals throughout the day

- Getting enough sleep every night

- Routinely taking part in some form of exercise

- Keeping a positive attitude

- Handling tiring tasks in the morning when your energy level is higher

To protect those around you from getting hepatitis C, you should:

- Avoid sharing personal items that may carry traces of your blood, such as razors, toothbrushes

- and nail clippers

- Cover any cuts or sores that you may have

- Tell all of your health care providers (including dentist) that you have the condition

- Abstain from donating blood, organs or other bodily tissues and fluids

- Use latex condoms during sex, especially if not in a long-term, monogamous relationship

It may be necessary to be vaccinated against hepatitis A and B. (There is no vaccine available for hepatitis C.) In addition, you should consult your doctor before taking any over-the-counter medications, dietary supplement or herbs.

American Liver Foundation, 800.465-4837, www.liverfoundation.org

Hepatitis Foundation International, 800.891.0707, www.hepfi.org

Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 800.891.5389, www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc

Hyperplastic Colon Polyps

| Your doctor has determined that you have one or more hyperplastic colon polyps, which are generally benign, or non-cancerous, growths on the lining of your large intestine.

Polyps are small clusters of extra tissue that form on the lining of the colon. These growths often resemble the cap of a mushroom and project outward from the wall of the intestine. Anyone can develop colon polyps, and about 20% of adults who are middle-aged and older have one or more polyps. Risk factors include:

ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease Nearly 90% of all colon polyps are hyperplastic polyps, which Other types of polyps include adenomatous polyps, from which 95% of colon cancers arise. These polyps are larger than hyperplastic polyps. Hamartomatous polyps and inflammatory polyps are two other types of benign colon polyps |

The usual treatment for hyperplastic colon polyps is removal, which may be accomplished in one of several ways depending on their size and location.

The following treatment methods are most commonly used:

Polypectomy – Excision of colon polyps, or polypectomy, during endoscopy is the method used to remove the vast majority of hyperplastic polyps. Endoscopic polypectomy is performed using a camera (endoscope) inserted through the anus and an electrified wire loop to remove smaller polyps. Other and larger or difficultly situated polyps are removed by laparoscopic polypectomy, which is performed using a camera (laparoscope) inserted through the abdominal wall. Laparoscopic polypectomy requires a few small abdominal incisions to provide access for the camera and surgical instruments.

Laparotomy – When necessary, a laparotomy is performed to excise colon polyps. This operation involves making a single, large abdominal incision to reach and remove the polyps.

Total Resection – In rare cases in which the colon is involved by numerous polyps, an operation to remove the entire colon and rectum may be required, called a total resection. After this procedure, a pouch is created from the end of the small intestine that is attached to the anus to allow waste to leave the body.

Polyps that are removed are sent to a pathologist to check for any signs of colorectal cancer. Your doctor will share the results of that testing with you and likely recommend that you have periodic colorectal cancer screening exams to monitor your health

Steps you can take to maximize your health and reduce the risk of developing more colon polyps or colorectal cancer include:

- Eating a low-fat diet high in fruits, vegetables and whole grains

- Avoiding the use of tobacco

- Limiting consumption of alcohol and red meat

- Taking part in some form of exercise

- Maintaining a healthy body weight

It is also believed that taking in more calcium and folate (or folic acid) can reduce the risk of developing colon polyps. Good dietary sources of calcium include low-fat dairy products and green, leafy vegetables. Folate is found in foods such as dried beans, citrus fruits and juices and fortified cereals. In addition, aspirin may be helpful in preventing colon polyps and gastrointestinal cancer, but it can be irritating to the lining of the stomach. Talk with your doctor about what medications are best for your individual situation.

American Cancer Society, 800.227.2345, www.cancer.org

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

National Cancer Institute, 800.422.6237, www.cancer.gov

Oncology Channel, www.oncologychannel.com

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

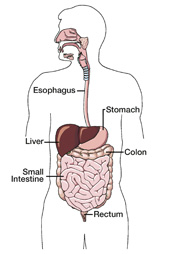

| Your doctor has determined that you have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), an ongoing (chronic) inflammation of the digestive tract. IBD has two main forms: Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis — which are different conditions that share some of the same symptoms and complications. You should talk with your doctor about your specific type of IBD. Both forms of IBD inflame the lining of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and may cause severe bouts of diarrhea and abdominal pain. Crohn's disease can affect any part of the GI tract from the mouth to the rectum, most typically the small intestine and colon, and spread deeply into the layers of affected tissue. The condition occurs sporadically, with normal healthy areas found in between diseased areas. Ulcerative colitis only primarily involves the lining of the colon, and occurs in a more evenly distributed pattern. The inflammation usually starts in the rectum and lower colon, but can involve the entire colon. IBD affects people of all ages but primarily occurs in those under the age of 35. Some 1 million Americans have the condition, with males and females impacted equally. Cases are evenly split between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. No one knows what exactly causes IBD, but possible contributing factors include a person's: Immune System – Some researchers believe that bacteria or a virus may lead to IBD through the body's resulting immune system response. However, the condition is not thought to be contagious. Heredity – IBD tends to run in families and affects certain ethnic groups more than others, especially Jews of European descent. The risk of developing IBD is 10 times higher in people who have a relative with the condition, and 30 times higher if the relative is a brother or sister. Environment – Environmental factors such as a high-fat diet may play a role in the development of IBD, which occurs more among people who live in cities and industrial nations. IBD affects each patient differently. Some have infrequent, mild attacks and their condition stays in remission (not active) for many years. Others have longer-lasting, more severe symptoms that can interrupt daily activities and sleep, sometimes requiring hospitalization or surgery. Patients with long-term IBD are at a higher risk for developing colon cancer, including those in remission. Without proper treatment for the condition, IBD complications can include: • Intestinal blockage |

There is no definitive medical cure for IBD, but a variety of therapies can be of help in reducing symptoms and achieving long-term remission. The following treatment options are available:

Everyday Changes – Although food and stress are not direct causes of IBD, people with the condition can diminish symptoms by eating soft, bland, low-fat foods rather than spicy and high-fat items, especially during flare-ups. IBD patients should also eat several smaller meals spread throughout the day, drink plenty of liquids and limit dairy products if they are lactose intolerant. It is also beneficial to minimize stress by getting enough sleep every night, taking part in some form of exercise and using relaxation techniques, such as deep breathing and biofeedback.

Medication – Drug therapy for IBD helps lessen inflammation and reduce symptoms but does not prevent long-term complications. Medications used include anti-inflammatory drugs, immune modifiers and antibiotics. Anti-inflammatory drugs are usually the first step in treating IBD and often work well for patients with mild to moderate symptoms. Corticosteroids are a type of anti-inflammatory drug sometimes given to people with moderate to severe IBD. Immune modifiers suppress the body's immune system response to reduce the inflammation and are generally given to patients who have limited success with anti-inflammatory drugs. They also can be used to help maintain remission. Antibiotics are given specifically to people with Crohn's disease. Other medications may also be recommended, such as pain relievers, iron supplements or vitamin B12 injections. New medications to treat IBD are currently being studied.

Surgery – Operations to treat IBD are performed when drug therapy is ineffective or there are intestinal obstructions or other complications. Sometimes just the diseased segment of the bowel is removed during a colon resection. At other times, surgical removal of the entire colon (colectomy) is performed — an effective way to alleviate ulcerative colitis. Surgery for Crohn's disease is not considered a permanent solution because the condition usually recurs after surgery.

You can choose to take an active role in your health and well-being. Learn as much as you can about your condition and have a list of questions ready each time you meet with your doctor. Join a support group for IBD and talk with your family, friends or counselor as you feel comfortable. Other steps you can take include:

• Finding out ahead of the time where restrooms are in the public places you plan to visit

• Making sure that you have a proper supply of medication at all times, especially when traveling

• Following your doctor's instructions and reporting any new symptoms promptly

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America, 800.932.2423, www.ccfa.org

Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 800.891.5389, www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc.

lschemic Colitis

| Your doctor has determined that you have ischemic colitis, an injury of the colon that results from reduced blood flow to the intestine. Ischemic colitis can range from mild or moderate with few symptoms to extremely severe and life-threatening. The condition most often affects people age 50 and older. The colon, or large intestine, is a tube lined with muscles that extracts moisture and nutrients from food, storing the waste matter until it is expelled from the body. It is typically 5–6 feet long in adults. The last segment of the colon is called the rectum. Ischemic colitis occurs when there is a blockage of the blood flow in an artery that supplies the colon, causing damage to the intestinal lining and layers. Occasionally the blockage happens in a vein. Ulcers (open sores) frequently result from the colon damage. Contributing risk factors may include atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries), hernia, surgical scar tissue, blood clots, low blood pressure, certain conditions such as lupus or sickle cell anemia and various medications that include blood vessel constrictors and birth control pills. Ischemic colitis can be acute, coming on suddenly, but is more often chronic, developing gradually and persisting. Sometimes when the cause is a blood clot, the colon's blood flow can be cut off totally and rapidly, a serious medical emergency. Symptoms of ischemic colitis may include abdominal tenderness, bloody diarrhea, an urgent, frequent need to have a bowel movement and sudden but usually mild abdominal cramps, often after eating and on the left side. In severe cases patients may experience dangerous infections, bleeding, gangrene (tissue death) or intestinal rupture. Because ischemic colitis symptoms are similar to those of other conditions, your doctor may want to perform one or more tests to confirm your diagnosis, which could include the following: • Ultrasound |

The treatment plan for ischemic colitis depends on the severity of the condition. The main goal of treatment is to restore the blood supply to the colon.

For less severe cases, patients are placed on either a very limited diet or intravenous fluids for one or two days to give the colon time to rest. Antibiotics are also given as a precaution to prevent serious infection. The majority of the time the condition clears up within two weeks.

In more severe cases, colon resection surgery is performed to eliminate or bypass the blood flow blockage as well as remove any part of the intestine that is damaged. The colon is then reconnected. When that is not possible, a colostomy is created to allow waste to leave the body through the abdominal wall to be collected in a bag.

If an underlying medical disorder contributed to the development of ischemic colitis, it will also be treated. Any medications that played a role in the condition may be stopped as well. Talk with your doctor about what medications are best for your individual situation.

Because ischemic colitis can be a sign of atherosclerosis, you should take the following steps to maximize your general health and minimize your risk for heart attack and stroke:

• Eat a low-fat diet high in fruits, vegetables and whole grains

• Avoid the use of tobacco

• Take part in some form of exercise

• Maintain a healthy body weight

Also, be sure to take all medications as prescribed by your doctor and promptly report any new

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 800.891.5389, www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc

Lymphocytic Colitis

| After completing a thorough lab analysis of your recent colon biopsy, a specialized doctor called a pathologist reported a diagnosis of lymphocytic colitis, an ongoing (chronic) inflammation of the colon. Lymphocytic colitis does not increase the risk of developing colon cancer and it is not cancer. Lymphocytic colitis is a rare condition that falls under the broad category of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It most often affects people between the ages of 50 and 70, and occurs equally in women and men. The colon, or large intestine, is a tube lined with muscles that extracts moisture and nutrients from food, storing the waste matter until it is expelled from the body. It is typically 5–6 feet long in adults. The last segment of the colon is called the rectum. Lymphocytic colitis occurs when lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, accumulate between the cells that line the colon and produce inflammation. The condition causes chronic and watery, non-bloody diarrhea and sometimes painful abdominal cramps and nausea. This happens on a continuing basis for some patients and occasionally for others. The inflammation of lymphocytic colitis is not visible when looking at the surface of the colon during a colonoscopy, but is apparent when colon tissue samples are viewed under a microscope. As a result, it is referred to as a microscopic form of colitis. No one knows exactly what causes lymphocytic colitis, but the condition appears to stem from an overactive immune system response to something that affects the colon lining. Triggers may include an infection with bacteria or a virus, or the prolonged use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and naproxen. Many patients with lymphocytic colitis have other autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, thyroid disease, pernicious anemia (the inability to absorb vitamin B12 from the gastrointestinal tract) or celiac disease, a digestive condition caused by intolerance to gluten, a protein found in foods including wheat and rye. Lymphocytic colitis is not life-threatening; however, heavy diarrhea caused by the condition can sometimes lead to severe dehydration, malnutrition and weight loss. |

The treatment plan for lymphocytic colitis often depends on the severity of the condition. The following treatment possibilities are available:

Everyday Changes – Although food is not a direct cause of lymphocytic colitis, people with the condition can diminish symptoms by eating a low-fat diet that is high in fruits, vegetables and fiber and avoiding caffeine and dairy products. It is also helpful to avoid the use of NSAIDs.

Medication – A variety of medications can be used to treat lymphocytic colitis. They include drugs to control diarrhea, anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics and corticosteroids, which are primarily prescribed to patients who do not respond well to other medications.

Surgery – In very rare and severe cases of lymphocytic colitis, an operation to bypass the large intestine (colon resection) or remove it entirely (colectomy) may be performed.

You can choose to take an active role in your health and well-being. Learn as much as you can about your condition and have a list of questions ready each time you meet with your doctor. Join a support group for IBD and talk with your family, friends or counselor as you feel comfortable.

Other steps you can take to maximize your health include:

• Burning up all of the calories you take in each day through healthy eating and regular exercise

• Minimizing stress by getting enough sleep every night and using relaxation techniques

• Cutting out the use of tobacco and limiting your alcohol consumption

• Visiting your doctor regularly and promptly reporting any new symptoms that develop

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America, 800.932.2423, www.ccfa.org

Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 800.891.5389, www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc

Melanosis Coli

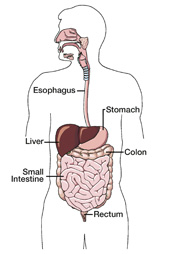

| After completing a thorough lab analysis of your recent colon biopsy, a specialized doctor called a pathologist reported a diagnosis of melanosis coli, an abnormal discoloration of the lining of the colon. Melanosis coli is not cancer and does not appear to increase the risk of developing colorectal cancer. The colon, or large intestine, is a tube lined with muscles that extracts moisture and nutrients from food, storing the waste matter until it is expelled from the body. It is typically 5–6 feet long in adults. The last segment of the colon is called the rectum. Melanosis coli occurs when the normally pink-colored lining of the colon turns dark brown or black from an accumulation of pigment in its connective tissue layer. The condition is often discovered during a routine colorectal cancer screening exam using a camera (endoscope) inserted through the anus. The principal cause of melanosis coli is the ongoing use of stimulant laxatives to treat constipation. Such laxatives are only intended for occasional use. Melanosis coli does not generally cause any symptoms; however, some health concerns may arise from the condition, most notably laxative dependence. The abuse of laxatives can result in the degeneration of intestinal nerves and dulling of natural bodily responses that stimulate bowel movements. When this happens, the colon instead relies on the laxatives to bring on bowel movements. In addition, the ongoing use of laxatives may cause a potassium imbalance in the body, which in rare cases can become a serious health threat. |

No medical treatment is necessary for melanosis coli. Patients are advised to stop taking laxatives, which usually reverses the discoloration of the colon after a fairly short period of time.

If constipation — generally defined as the passage of small, hard and dry bowel movements fewer than three times a week — is an ongoing problem, your doctor may suggest that you take fiber supplements, which are safe for long-term use. Be sure to talk with your doctor about what choices are best for your individual situation.

You can reduce the occurrence of constipation by addressing the key factors that contribute to the condition: low fiber and water intake and a sedentary lifestyle.

Be sure to eat a low-fat diet high in fruits, vegetables and whole grains and to drink about two quarts of fluids (mostly water) each day. Also, take part in some form of regular exercise, especially activities that engage the abdominal muscles (e.g., walking on an uneven path rather than a flat, even surface). In addition, you should not ignore the urge to have a bowel movement.

Other steps you can take to maximize your health and reduce the risk of developing colorectal and other types of cancer include:

• Avoiding the use of tobacco

• Limiting consumption of alcohol and red meat

• Maintaining a healthy body weight

• Getting enough sleep every night

• Visiting your doctor regularly and promptly reporting any new symptoms

American Cancer Society, 800.227.2345, www.cancer.org

eCureMe, (323) 731-9200, www.ecureme.com

Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 800.891.5389, www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc

Radiation Colitis

| Your doctor has determined that you have radiation colitis, an inflammation of the colon that occurs as a side effect of cancer radiation therapy to the abdomen or pelvis. The condition can arise from external radiation treatment delivered by a high energy X-ray machine or internal radiation therapy, which is delivered through small implants placed directly into or near the cancerous tumor. The colon, or large intestine, is a tube lined with muscles that extracts moisture and nutrients from food, storing the waste matter until it is expelled from the body. It is typically 5–6 feet long in adults. The last segment of the colon is called the rectum. Radiation colitis occurs when an increasing number of cells in the colon die as a result of radiation therapy. Often the doses of radiation that cause colon injury are very close to the doses needed to treat cancer in the abdomen or pelvis. The severity of the condition depends on the size of the radiation dose and other factors such as the frequency of treatment and tumor size. Radiation colitis can be acute, coming on suddenly, or chronic, developing gradually and persisting. Most of the time, patients with acute radiation colitis develop symptoms within eight weeks of starting their treatment. With the chronic form of the condition, symptoms may not arise until months or years after radiation therapy is over. Symptoms of radiation colitis may include abdominal cramps, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, frequent urges to have a bowel movement, rectal bleeding, weight loss and fatty stools. Complications can develop, especially in chronic radiation colitis, such as: • Intestinal blockage Although the cause of radiation colitis is cancer radiation therapy, other risk factors can increase the risk of radiation injury to the colon such as surgical scar tissue, high blood pressure, diabetes, atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) and underlying inflammatory bowel disease. |

The treatment plan for radiation colitis often depends on the specific symptoms and severity of the condition. The following treatment possibilities are available:

Everyday Changes – Although food is not a direct cause of radiation colitis, people with the condition can diminish symptoms by eating a low-fat and low-fiber diet, drinking plenty of fluids and avoiding certain foods, caffeine and dairy products. Iron or other nutritional supplements may be needed, as well. Patients are also encouraged to get plenty of rest.

Medication – A variety of medications can be used to treat radiation colitis. They include drugs to control diarrhea, nausea and bleeding, pain relievers, and steroid foams that help relieve rectal inflammation and irritation.

Surgery – In very rare cases of severe radiation colitis, an operation to bypass the large intestine (colon resection) or remove it entirely (colectomy) may be performed.

Other medications and procedures to treat and prevent radiation colitis are currently being studied.

You can choose to take an active role in your health and well-being. Since nutrition has an impact on radiation colitis, you should start a low-fiber, low-fat diet the first day of radiation therapy and continue it for two to three weeks after treatment, when symptoms of the condition usually subside.

Other steps you can take to maximize your health and minimize symptoms include:

• Eating smaller, more frequent meals with foods at room temperature

• Drinking three quarts of liquids each day to prevent dehydration, which can include apple and grape juices and flat, non-caffeinated carbonated drinks

• Limiting dairy products (except buttermilk, yogurt and processed cheese)

• Avoiding whole-grain bread and cereal, raw vegetables, fresh and dried fruit and nuts, seeds and coconut

• Adding nutmeg to your food to slow the digestion process

• Avoiding smoking, alcohol, caffeinated beverages, chocolate and fatty, fried, refined and highly seasoned foods

• Eating foods such as broiled or roasted fish, meat and poultry, eggs, macaroni and noodles, white bread and toast, smooth peanut butter, bananas, applesauce, baked, broiled or mashed potatoes and mild cooked vegetables such as asparagus tips, green beans, carrots, spinach and squash

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

National Cancer Institute, 800.422.6237, www.cancer.gov

Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 800.891.5389, www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc

Stomach Cancer

| After completing a thorough lab analysis of your recent stomach biopsy, a specialized doctor called a pathologist reported a diagnosis of stomach cancer, or cancer that begins in the stomach. Also called gastric cancer, the condition is most often diagnosed between the ages of 60 and 80. It occurs twice as often in men than women and affects some ethnic groups more frequently than others, especially Asian/Pacific Islanders, Hispanics and African-Americans. The stomach is a hollow, muscular pouch in the upper-left region of the abdomen, typically 10 inches long in adults. Its main purpose is to process and store food. The walls of the stomach contain layers of muscles and glands that produce enzymes and gastric acid to aid in digestion. Cancer occurs when cells in the lining of the stomach do not develop and die in their normal manner. The extra cells that result form a growth, or tumor, which can be benign or malignant. Benign tumors are not cancer and do not spread throughout the body. Malignant tumors are cancer. Their cells may invade and damage surrounding areas or spread to other locations in the body (metastasize). Contributing risk factors for stomach cancer may include: • Being age 50 and older The most common type of gastric cancer forms in the innermost stomach layer and is called adenocarcinoma. It accounts for about 95% of all cases. Rare types of stomach cancer include lymphoma and leiomyosarcoma. Because stomach cancer is often diagnosed at a later stage, your doctor may want to perform one or more tests to help determine if the cancer has spread, which could include the following: • MRI Scan Cancer that is confined within the stomach wall is the most manageable and curable. If malignant cells extend through the stomach into surrounding tissues, lymph nodes or other areas of the body, the treatment plan will be more complex and the cancer may not be curable. Many treatment options are available for patients with incurable stomach cancer to help minimize pain and improve quality of life. |

Deciding on a treatment plan for your stomach cancer can be complex and depend upon a variety of factors, such as your age, general health condition, stage of cancer and personal preferences. Sometimes more than one type of therapy may be used. The following treatment possibilities are available:

Surgery – Three main surgical procedures are used to treat stomach cancer: endoscopic mucosal resection, partial gastrectomy and total gastrectomy. Endoscopic mucosal resection to remove the tumor is performed only in cases of very early stage cancer and involves the use of a camera (endoscope) inserted through the mouth. In partial, or subtotal, gastrectomy, a portion of the stomach is removed along with surrounding tissues and nearby lymph nodes. The remaining sections are then joined together. In total gastrectomy, the entire stomach is removed along with surrounding tissues and nearby lymph nodes. The small intestine is then connected to the esophagus and a new "stomach" is created from intestinal tissue if possible.

Radiation Therapy – Another treatment method for stomach cancer is radiation therapy, which can be delivered externally or internally. In external beam radiation, a high energy X-ray machine is used to direct radiation at the tumor. Internal radiation therapy destroys cancer cells with small implants that are placed directly into the tumor. Radiation therapy can also help reduce stomach cancer symptoms such as pain, bleeding and difficulty eating.

Chemotherapy – The use of anti-cancer drugs, or chemotherapy, provides a way to slow tumor growth and reduce pain for patients whose cancer has spread outside of the stomach.

You may also consider participating in clinical trials. These investigative studies help doctors learn about new treatments and better ways to use established treatments. Talk with your doctor about the possibility of taking part in a clinical trial in your area.

You can choose to take an active role in your health and well-being. Learn as much as you can about your condition and have a list of questions ready each time you meet with your doctor. Join a cancer support group and talk with your family, friends, clergyperson or counselor as you feel comfortable. Also, be sure to get enough sleep and eat healthy foods every day.

In addition, you should report any new symptoms promptly to your doctor, who will likely recommend periodic screening exams to monitor your health.

American Cancer Society, 800.227.2345, www.cancer.org

American College of Gastroenterology, 301.263.9000, www.acg.gi.org

National Cancer Institute, 800.422.6237, www.nci.nih.gov

Oncology Channel, www.oncologychannel.com

This patient resource sheet is provided to you as a service of CBLPath® and is intended for information purposes only.

It is not meant to serve as medical advice or a substitute for professional medical care. Treatment options may vary,

and only you and your physician can determine your best treatment plan.

© 2005 CBLPath, Inc